In the study of martial arts we often find a tension between form and creativity.

For the beginner, form is an essential study. By form we mean things like learning where to place your feet, how to strike, or, more generally, how to move so that you’re executing a technique correctly.

You can think of form as the paint-by-numbers outline of correct movement for a given martial art technique: place your hand here, step here, and so on.

As a martial artist’s practice deepens, they move beyond form and into the realm of creativity. The paint-by-numbers outline is slowly replaced by a blank page, full of potential, upon which the practitioner can create their own unique work.

For Mitsugi Saotome Shihan, the founder of the Aikido Schools of Ueshiba (ASU), creativity is a fundamental aspect of how he teaches Aikido.

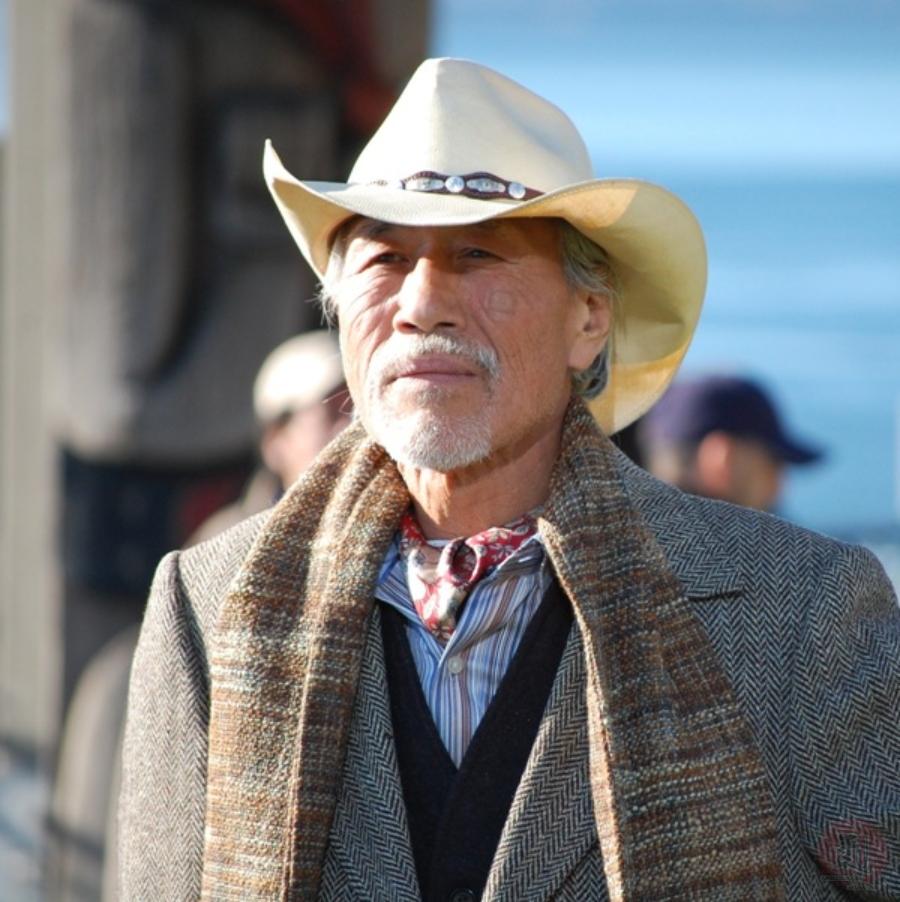

Mitsugi Saotome Shihan

Saotome Sensei is one of the oldest living students of the founder of Aikido, Morihei Ueshiba Sensei, commonly known as O-Sensei. He has been teaching Aikido for over fifty years and throughout that time he has emphasized the importance of creativity.

This emphasis on creativity runs deeply through the entire organization of ASU, manifesting in many different ways.

In this article we’re going to look at how Saotome Sensei’s emphasis on creativity has shaped his approach to Aikido, how he has incorporated creativity into his teaching, and how we might be able to take these lessons and apply them more generally to our lives.

The Tension Between Form and Creativity

In the study of any art you begin by learning the mechanics.

This process starts at the specific—the form—and then, over time, zooms out to more global considerations, and then, finally, to a level of mastery over form that allows for creative expression.

As Pabo Picasso said, “Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

If you want to get better at drawing, you might start by learning how to hold the pencil correctly, and from there you might progress to learning how to draw lines of different weights, and so on.

Studying Aikido—or any martial art—is often imagined as working the same way.

First you start by learning how to stand, how to strike, and how to make sure you’re maintaining good posture. Only after you have mastered these basics of form can your practice expand into creativity.

But a unique aspect of Saotome Sensei’s teaching is that he has always eschewed this linear path and emphasized creativity from the very beginning—even with fairly new students.

I remember Saotome Sensei led a beginner’s workshop when I was just trying to get my dojo up and going. 15 or so people showed up and to my shock he was having everybody, all these new students, just rolling all over the mat. He didn’t really explain anything at first, he just had them start moving. And I was just like, ‘Oh my God! People are going to hurt themselves.’ But everyone was fine. He was emphasizing the principles of the movement, not the specific technique. And it really worked.

– Raso Hultgren Sensei, ASU Senior Instructor

There is an important distinction to make here.

In his teaching, Saotome Sensei does not ignore form and correct mechanics. Rather, he teaches them in the context of natural movement.

We all live in our bodies, and in some innate way our bodies know how to move correctly (although it may take some priming to get them to do so).

While it’s important to be shown how to hold your arms, or where to put your feet, the more global consideration of making sure the movement makes sense in your entire body—that your body maintains a creative freedom, even in the midst of learning a basic form—is crucial to the approach that Saotome Sensei takes in his teaching.

Another way to frame this aspect of Saotome Sensei’s teaching is by focusing on the principle beneath the form.

If you’re thinking about the principle—the why behind the form, which describes the design or idea driving the mechanics of the movement—then you can potentially bypass the robotic repetition of form, and access your creative potential. And you can study this even if you haven’t mastered the form yet.

“I Don’t Want Clones”

If you’ve ever attended an Aikido seminar taught by Saotome Sensei, you’ve probably heard him say, “There is no Aikido style. There is no my Aikido, there is no Saotome Sensei style.”

Along the same lines, you might also have heard him say, “I don’t want clones.”

What Saotome Sensei is driving at in these statements is an approach to Aikido that he’s taken his entire career.

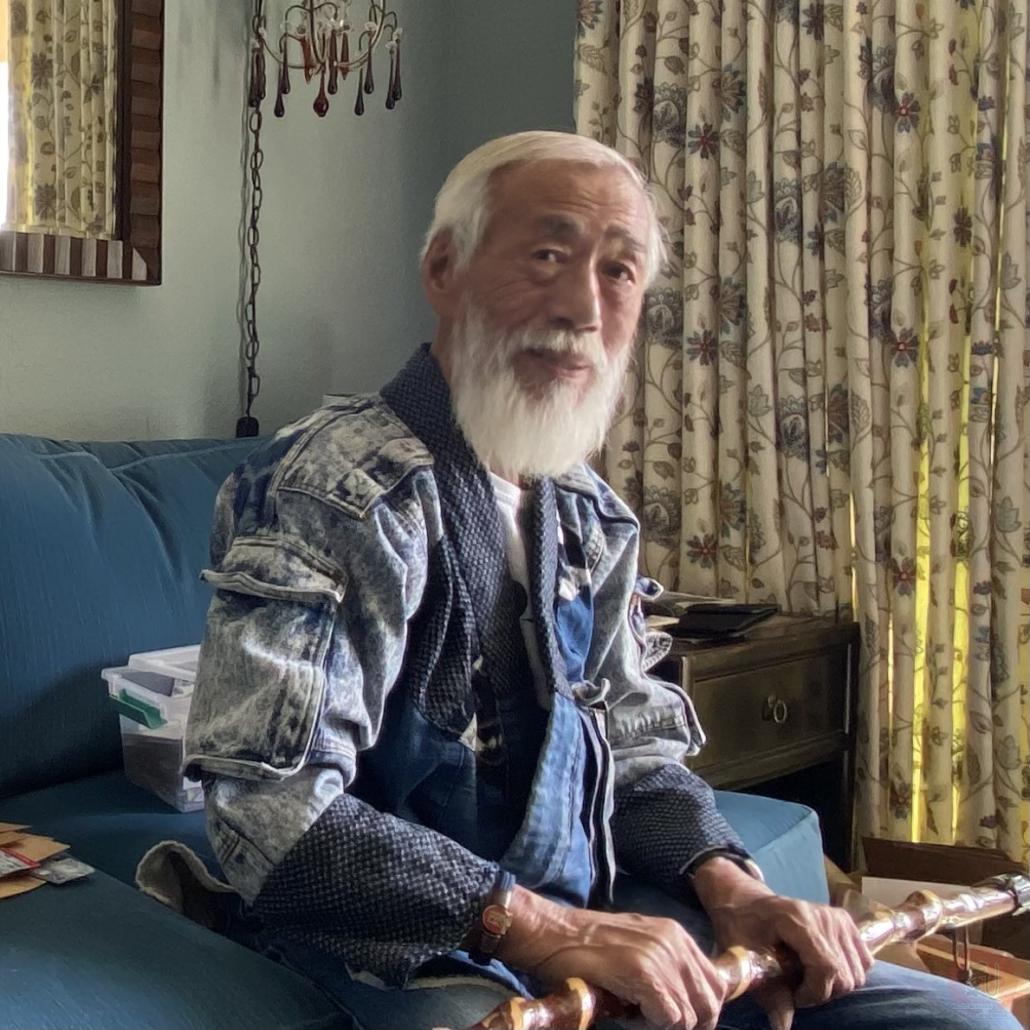

Photo credit: George Ledyard Sensei

Where some Aikido teachers emphasize the importance of copying their movement until students get to a certain level of ability—that is, of mastering the form by repeating it exactly as they see it—Saotome Sensei has instead cultivated a focus on each student finding their own way of doing the movements that works with their unique bodies and characters.

This emphasis on individuality has resulted in ASU cultivating a diverse range of senior instructors, many of whom are now shihan themselves.

When you see ASU instructors do Aikido, you can tell they have a variety of approaches to how they execute different techniques, as well as how they teach. The unifying principle between all of them, and across all ASU dojos, is a focus on natural movement and the principles underlying the techniques being studied.

This emphasis on creativity among ASU’s instructors makes it somewhat unique among Aikido organizations throughout the world.

While some organizations have a strong focus on cultivating the same “look” in how every teacher and student executes a technique, ASU has instead cultivated an approach that elevates underlying principles and finds a way to make manifesting them work for each individual student.

All of this is very much by design.

Starting in the early days of his teaching over fifty years ago, and continuing on to the present day, Saotome Sensei has been working to cultivate students who are not clones, but who have found ways to manifest their own individual expressions of the universal principles that underpin Aikido as a martial art.

The underlying focus is on self-exploration. Senior instructors at ASU encourage students to do whatever might facilitate that process, whether it’s studying nature, studying their relationships, or studying their own personal connection to Aikido.

If approached with an open mind and a creative attitude, all of these other practices can inform one’s Aikido practice.

How to Teach Creativity in Martial Arts

One underlying idea in Saotome Sensei’s emphasis on creativity is that each student—and each teacher—must find their own way to access the practice of Aikido within their individual bodies.

The goal is not to produce robots who can correctly copy a certain way of moving, but to cultivate an inner creativity so that students move spontaneously in reaction to each individual encounter.

Saotome Sensei’s teaching is steeped in creativity. That’s the way he looks at the world. He does not like to repeat the same thing over and over.

– Ania Small Sensei, ASU Senior Instructor

To help students grow their creativity on the mat, Saotome Sensei avoids repetition in his teaching, trying to get people to imagine various scenarios in order to keep their practice fresh.

An Aikido dojo might have a limited choice of weapons—a bokken, a jo, or a tanto are the typical list for most Aikido dojo. But in a street fight, anything goes. A pencil or a broken bottle can become lethal, and a rock could be your attacker’s first weapon of choice.

For this reason, Saotome Sensei will often pose “what if” questions while teaching.

What if you were training in a narrow hallway and had limited movement? What if you were attacked in a crowd? What if you were facing multiple attackers in an open field, with the sun at your back?

Beyond questions about surroundings and environment, there are variables like the size of the attacker and how exactly they are attacking.

You need to be creative. Sometimes people think they’ve made a mistake on the mat. But it’s not a mistake—it’s just that they’re responding to a different situation than the one they were presented with.

– Saotome Sensei

The point of all these questions and considerations isn’t for the student to prepare for a thousand individual scenarios.

It’s that there are an infinitude of scenarios that could arise, and the only way to be ready for them is to cultivate a freedom of movement that allows you to respond in the moment to whatever might be happening. That is, to cultivate creativity in your Aikido practice.

Further, each encounter between an uke and a nage is unique because each person’s body is unique. The emphasis isn’t on whether each person is short or tall, strong or weak, but on the specific encounter and responding to it naturally.

Just like all the scenarios mentioned above—being attacked in a hallway, in a field, and so on—the two people that meet each other in an encounter are also unique, creating an individual encounter that should be met with the creativity demanded of the moment rather than a planned response that has been drilled the same way through hours of repetition.

As Saotome Sensei’s teaching has evolved, his emphasis on spontaneity and creative movement has only grown stronger.

Lately, when teaching at seminars, Saotome Sensei will often demonstrate a free-flowing response to attacks, in which the techniques change fluidly and don’t follow a rote pattern. And then he’ll have his students do the same.

Saotome Sensei and Art

Saotome Sensei’s creativity doesn’t just manifest in his Aikido.

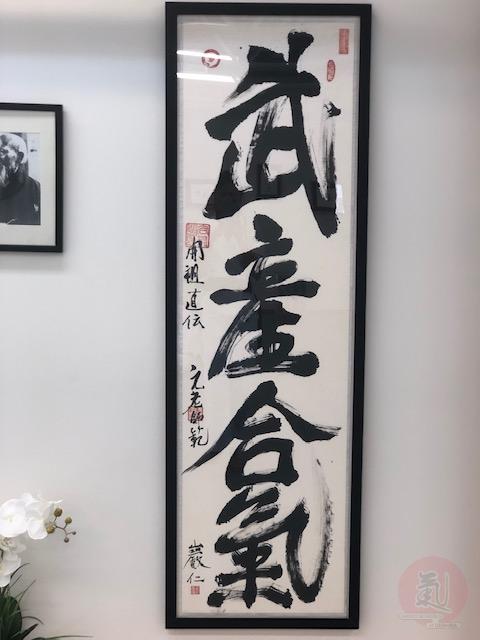

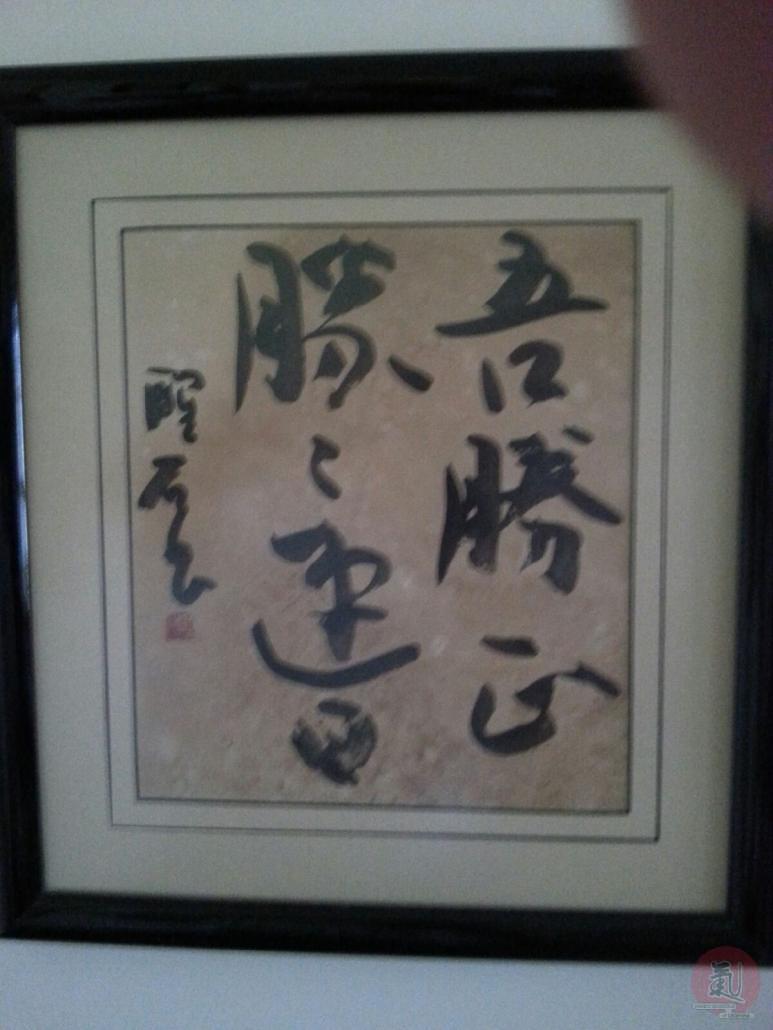

He is also a prolific artist who does work in a variety of mediums, including calligraphy, woodwork, and sculpture, and he also sews his own clothes.

Here are some examples of Saotome Sensei’s work:

Shu Ha Ri

In Japanese, the phrase Shu ha ri describes the evolution from form to creativity in a martial arts practice.

Saotome Sensei has written about Shu ha ri in his book Light on Transmission, so we will close this article by quoting his words on the subject.

Shu

In the martial arts, the first order of learning is called shu, which means to observe or abide by established guidelines or rules. Shu is the learning of waza, or rules, by practicing their kata, or forms.

Ha

The next order of learning is ha, meaning to break apart or violate the established form. In ha, one reexamines the movements of the kata in order to discover their limits.

Ri

The final order of learning is ri, which means departure or separation. One only encounters ri after becoming thoroughly proficient in the execution of waza and their reversals. Ri indicates the ability to freely adapt and apply waza to different situations and to single and multiple opponents. It requires that one distance oneself from the rules one has learned in earlier phases of training and that one study how to respond flexibly and intuitively to a wide range of attacks.

*Excerpted from pages 79 and 80 of Light on Transmission, by Mitsugi Saotome Sensei

Saotome Sensei and Creativity—Stories from His Students

While working on this article we spoke to several of Saotome’s Senior students.

Here are some of the memories about Saotome Sensei and how he incorporates creativity and a broader perspective about natural movement into his Aikido and his teaching.

On the Importance of Correct Form

I started studying Aikido in Poland, and then I traveled a lot and visited several dojos in England and in the United States.

Everywhere I went, you would hear teachers say, “Do it like this, don’t do it like that.” This seemed to be a common attitude at many Aikido dojos—there was a right way to do things and it was everyone’s job to stop you from doing things the wrong way, and get you to start doing things the right way.

But when I started training at ASU under Saotome Sensei he didn’t correct me for a very long time. He didn’t tell me, “Oh no, not like that—do it like this.”

Sometimes he might make a suggestion, and point out a way you could try something. But it wasn’t because something was right or wrong.

And that approach has made a really big impression on me, and has shaped my Aikido practice and the way I teach Aikido.

– Ania Small Sensei

On the Purpose of Training

One time a group of us were out to dinner with Saotome Sensei after an Aikido class, and someone asked, “Sensei, what is the purpose of Aikido training? Why do we do it?”

Saotome Sensei often won’t answer questions like this directly, but instead will speak about a related subject.

But this time he did give an answer.

What he said was, “The purpose of training is for you individually and your community as a whole to grow.”

That was a deeply meaningful teaching moment for all of us at that dinner table. It showed us that there is a bigger project beyond what we’re doing on the mat, and that what we’re doing when we practice Aikido has all these connections to the rest of our lives. And that Sensei was invested in our entire growth as people, and in the growth and improvement of the dojo community, and not just in us Aikido students.

– Eugene Lee Sensei

On the Use of Imagery to Cultivate a More Creative Aikido Practice

Saotome Sensei has often exhorted his students to use imagery in their practice.

I remember in the early days of my Aikido practice, he shared that he pictures the movement of the galaxy when he’s doing certain movements in Aikido.

“This is the way the galaxy moves,” he said. “I’m not trying to make anyone move, this is just the movement of the galaxy.”

It was a kind of creative mimicry, a use of imagery to get at a more fundamental creative aspect of the practice.

Another time I was working with a bokken, and he gave me another imagery cue to help me—he said, “Raso, cut the moon!” That kind of image just allows the body to expand to tap more directly into the natural movement it already has and really access it.

And more recently, when it comes to using imagery in his teaching, I’ve heard Saotome Sensei say, “Catch the image. Use the image.”

– Raso Hultgren Sensei